Mongolia’s Must-See History

Housing the world’s most extensive collection of Chinggis Khaan objects, the Chinggis Khaan Museum places visitors in 13th century Mongolia to understand the storied Emporer within the context of his time.

In addition to focusing on Chinggis Khaan the person and ruler, the museum immerses visitors in the history of Mongolia’s—spanning centuries of peace developing a rich culture of horses, religion, and preserving nature.

The Largest Museum of Its Kind

The museum opened in late 2022 in downtown Ulaanbaatar on the site of the old Natural History Museum. Entirely brand new, the Chinggis Khaan Museum is the largest of its kind, the result of the greatest investment in a museum by Mongolia in the last 30 years.

The building itself is a great testament to the Mongols. The main gates resemble the shape of a Gerege (messengers pass). In Mongolia there’s a saying: “A family that is thriving can be seen from its gate.” The Gerege is a messenger’s pass that grants access to greater things. Once inside, the guests are to walk up the stairs to the third floor. On top of the stairs, there’s a large portrait of Chinggis, as if he’s to take you on a journey through the history of Mongolia.

Following the strict codes of the Mongolian traditions, soil samples from 10 sacred mountain and 21 sacred objects from 21 provinces of Mongolia were placed here during the commencement ceremony for setting the foundation stone. As ritual, this Mongolian tradition asks the spirits of the land to bless the museum.

The architecture is one of a kind. The top part of the museum is shaped like a Mongolian yurt or a ger, with the figure of a golden falcon on top. The front façade of the museum has 5 symbols, belonging to each of the kings who left their names in the history of Mongolia: Ogodei (third son of Chinggis), Tolui (youngest son of Chinggs), Chinggis Khaan, Munkh (grandson of Chinggis/son of Tolui) and Guyug (grandson of Chinggis/ son of Ogodei).

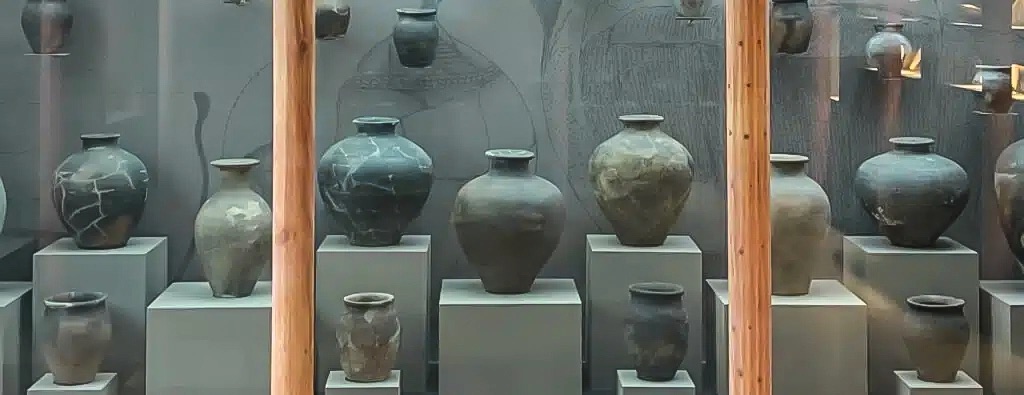

The museum has a total of 9 floors with more than 10,000 exhibits. More than 85% of the exhibits are original. Each floor has different periods of history and chronologically displays its exhibits, stanning from the Bronze age to the early 20th century.

Interactive Exhibits of Mongolian Culture

With a mission to build and protect the cultural heritage of Mongolia through the education and entertainment of museum audiences, the museum has its exhibition hall divided into chronologically into kingdoms that existed on the very soils of Mongolia.

These interactive exhibits, immersive galleries, and cinematic experiences are a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to engage with the history, culture and traditions of Mongolia’s past, present, and future.

The museum houses priceless objects belonging to the various empires of Mongolian history and with the correct tempered glass display case with humidifier and proper lighting, the exhibits have become more strikingly visible with details.

In addition to the clever interior designs, the interactive system of the museum is the AR system that will interactively read the exhibit displays and will be in 5 languages of the United Nations. All one must do is to download the app onto their cellphones and face the camera to the designated displays from the marked spots on each floor of the museum.

The first floor dramatically greets guest and leads you to the third floor, the Hall of the Ancient Empires, while the second floor houses the administrative offices, laboratory, and restoration rooms.

From the Bronze Age to the 12th Century

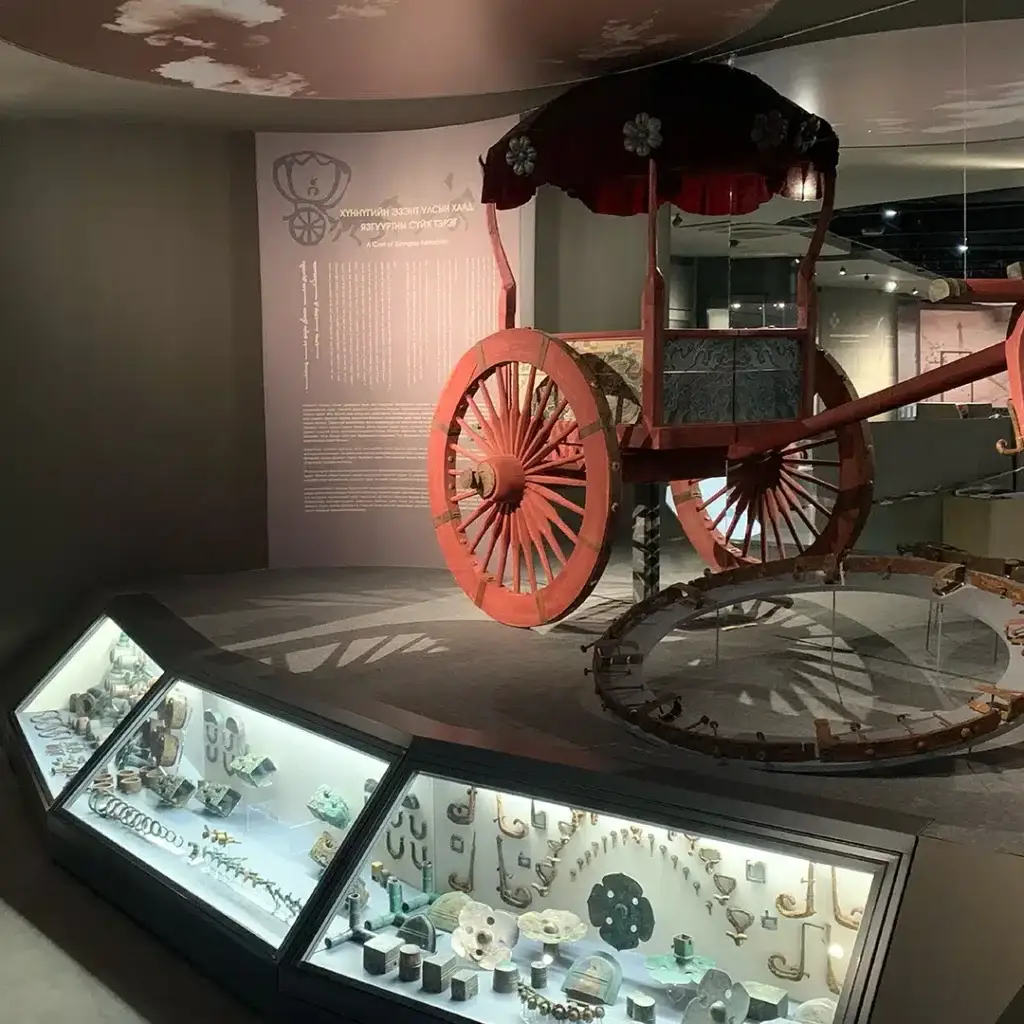

Hall of the Ancient Empires begins with exhibits of the Deer stones dating back to the bronze age. Along with other impressive exhibits of the Xiongnu empire (3rd century BC to 1st century AD). Many tombs of the Xiongnu were found, however the tomb interiors are not available to the public. Here is a recreation of the Xiongnu tomb of the King. The depiction of the tomb is highly accurate, and one can see how the body was placed in the coffin inside a large chamber of the tomb and what kinds of objects were buried with the person—including swords, ornaments, and finely detailed jewelry. The style of clothing found in the tombs indicate the advanced techniques in applique-style embroidery.

Xiongnu Empire’s Luut City aka “the dragon city” roof tiles are displayed as well. Many people think that the Xiongnu sword wielding warriors were strangers to an urban life. But the Luut City had a fortifying wall, an architectural marvel dating back 2,000 years. Defying beliefs that the Xiongnu were barbarians, the Xiongnu had a functioning society, a tax system, and were the ancestors to the great Atilla the Hun.

The fourth floor is reserved for the Jujan Empire of the 4th to 6th century, Tureg Empire of the 7th to 9th centuries, the Uighur Empire of the 8th to 9th centuries, and the Khitan Empire of the 10th to 12th centuries. All these three empires expanded from their territories and conducted trade with Central Asia and began to bring in many cultural works from Central Asia—namely statues, writings, human stones, worshipping grounds and the mechanism of the government.

The Tureg Empire is well known for erecting Steles for their kings and generals, along with stones depicting the noble people. The museum houses many of the “human stones,” which memorialized the court account of the accomplishments of the person.

One of the fine representations of the Tureg Empire is the Altai harp, a 5-stringed musical instrument. The body is made from birch tree, and it has a horse head carved on the top. It even has a writing in Runi (Orkhon inscriptions), clearly inscribed along the body of the harp.

One of the most intriguing marvels is a toothbrush dating back a thousand years, made of a wood handle and horsehair bristles.

The fourth-floor tour concludes with the with tomb findings of the Tureg Empire, one of the most significant discoveries in Mongolian archeology. The tomb was buried with over 330 objects, including miniature human dolls symbolizing the servants and the royal consorts to join the deceased ruler in the afterlife. Other findings include coins from the Byzantine Empire and artifacts belonging to China, India, and Tibet—a clear indication that the Tureg empire had diplomatic and trading relations with all the major countries of its era.

From Chinggis Khaan to Today

The fifth floor belongs to the Mongol Empire, the empire that Chinggis created. Visitors are able to see a replica of the Rashaan rock inscriptions of all the symbols of the Mongolian tribes—the stamps of the kings. There is a saddle that dates to the 13th century, belonging to Chinggis, its exterior ornately decorated with the teeth of a horse, which were cut into smaller thin pieces and shaped in hexagonal patterns and elaborately lined. No other saddle of its age and style has ever been found around the world.

Other incredible items include the helmet of a Mongolian general from the 13th century, an imperial passport, and a detailed family tree of Chinggis Khaan.

The sixth-floor houses exhibits from the successors of Chinggis Khaan—namely the Yuan dynasty of Khubilai Khaan, the Il Khanate of Khulegu Khaan, and the grand children of Chinggis Khaan. Visitors can see the clothing style of the era, writings from the period, and coins that were minted in the conquered lands.

On the seventh-floor, the exhibits show the history of Mongolia after the Yuan empire, which saw variously turbulent, peaceful, and poetic eras in history. Here visitors can see many Buddhist icons with many sacred sutras and texts.

There are many impressive artifacts from this era—including the swords of kings, the imperial seals, and banners. But a bronze figure of the Green Tara, a female goddess, is an exceptional piece made by the first Bogd of Mongolia, Zanazabazar, the direct descendant of Chinggis. Zanazabazar was the head of Mongolian Buddhism and a great artist, called the Michelangelo of Mongolia. One of his original masterpieces is this Green Tara. She’s sitting in the contemplative position, as if ready to spring into action for the good of the people.

The eighth floor offers artifacts that show how Mongolia participated in shaping the modern-day Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. Notably the exhibits demonstrate how Mongols were able to conduct advanced warfare on horseback and perform supreme skill at archery. Arrows dating back 300 years hang overhead as if set loose in unison. Here visitors can also see the Italian sword brought to the Yuan dynasty by Marco Polo.

Finally, on the top floor of the museum bestows a gilded portrait of Chinggis Khaan and an altar to him.

Many people around the world have a flawed sense of who Chinggis Khaan was, having learned about him and Mongols in general from distorted representations in movies.

What the museum does especially well is offer great insight to the unifying good he brought, the freedom he created by outlawing slavery, and how he created laws that protected the natural landscape and viewed the earth as sacred. The Mongols additionally left a profound mark in the world by introducing diplomacy, paper money, cross cultural communication, and respect for all religions.